Saturday, September 03, 2011

Saturday, May 14, 2011

The Great Shift East

Yet, practically without challenge, ever greater policy discussion today turns on the West (or the US) retaining international economic dominance: “Is the West history? What must we do to respond?”

That challenger to continued US hegemony is, of course, China.

Towards the end of 2010 China became the world’s second-largest economy, along the way overtaking Germany, the UK, France, and all the rest of Western Europe. Today, the economic strength of China is exceeded only by that of the US. By some accounts China today already consumes half the world’s output of refined aluminium, coal, and zinc; and uses twice the quantity of crude steel as does the EU, the US, and Japan combined.

India, the only other billion-people nation on the planet, has launched itself onto a similar growth path, after a half-century of moribund quiescence. These two giant economies now grow at a pace previously recorded only in easier-to-ignore, special-cased, tiny Far East Asian island nations. This emergence of the East has, in the last three decades, yanked the world’s economic center of gravity nearly 5000 km out of its 1980 mid-Atlantic location eastwards past Helsinki and Bucharest, onto a trajectory aimed squarely at India and China.

India, the only other billion-people nation on the planet, has launched itself onto a similar growth path, after a half-century of moribund quiescence. These two giant economies now grow at a pace previously recorded only in easier-to-ignore, special-cased, tiny Far East Asian island nations. This emergence of the East has, in the last three decades, yanked the world’s economic center of gravity nearly 5000 km out of its 1980 mid-Atlantic location eastwards past Helsinki and Bucharest, onto a trajectory aimed squarely at India and China.That global economy activity has moved east in this graphic fashion shows the rapid growth in incomes going to the large chunks of humanity who live in China, India, and the rest of East Asia. (Population itself changes much more gradually; this sharp east-directed rise of the rest does not come from just population growth.)

Together with this growth has been the lifting from extreme poverty of over 600 million people—a large and rapid improvement in the well-being of humanity unprecedented in the history of this planet.

But more is to come. Today, the income of the average person in the East is still lower than that of his counterpart in a dozen countries in Africa; his carbon footprint is less than one quarter that of the average American; and he is intent on making not just refrigerators and running shoes, but solar panels, wind turbines, and nano-cars cheaply enough that yet more of humanity can afford them.

What’s not to like?

But many policy-makers and observers in the West fail to share this optimism on the shifting global economy. Instead, they ask: Will emerging Asia now buy up all the West’s assets and use up all the world’s raw materials? Will emerging Asia soon command the entire world’s jobs, absorb the entire world’s investment? This is Rise of the Rest on a massive scale: What must the West do to respond?

Contrary to this alarmist view, there is, of course, always the possibility that this shift towards the East might, in truth, be only beneficial to the West.

But, independent of the eventual outcome, if now the East is indeed viewed as challenging the West, the correct question should not be what is good for the West or indeed for the East, but instead what is good for the planet. And if one side loses while the other side gains, compromise is needed: What contours frame that bargain?

In the alarmist scenario the West is overtaken in the next 10 years: So, how much would people in the West be willing to pay people in the East to prevent that? How much would the East have to be compensated to keep the West ascendant? How much of a disruption in the East’s development trajectory would the West consider justified for the West to remain Best?

The tradeoff, unfortunately, seems far from favourable.

China today faces possible trade reprisal even though its average citizen remains poorer than his counterpart in Belarus, El Salvador, and Jamaica, or for that matter, across 9 countries in Africa. If China kept its current average income but had the same population as, say, Namibia and were located on the African continent, China would today be a candidate for US foreign aid, not a potential rival for global hegemony. In the last 30 years China has lifted over 600 million people from extreme poverty: this is double the population of the US or the EU, ten times the population of the UK. In the last three global economic downturns, China has provided a growth boost to the world economy multiple times what the US failed to do. What good does it do the world if the West disrupted so successful a poverty-reducing machine, so effective a stabilizing influence for the global economy?

No one yet knows answers to the difficult questions on what is best for the world. But I suspect that considering them seriously will lead to optimism and hope for the changes given in the Figure. That shifting global economy has improved the well-being of humanity for the last 30 years: to overturn or even slow these changes now for short-term domestic gain can reveal only a tragic failure of global political vision.

Tuesday, May 03, 2011

A terrifyingly hostile place to be born a girl

When I wrote "How can hundreds of millions...", many readers, of course, quickly linked in their minds that gender imbalance to the many horrific tales one hears emerging from China's one-child policy. If 119 boys are born for every 100 girls - as usually reported for China - then that works out to 840 girls to 1000 boys. Given China's population of 1.3 billion, this means 24 million Chinese men of marrying age without spouses by 2020.

It is instructive if grim to note this gender bias is seen as well in the very differently-governed India where the 0-6 age group now has 914 girls to 1000 boys (down from 927/1000 in 2001), confirming how the country has become "a terrifyingly hostile place to be conceived or born a girl", pointed out to me by Vinayak @kayaniv.

Monday, April 25, 2011

How can hundreds of millions of something - anything - be scarce?

I sat next to Jim Rogers on a panel once (so you don't think I'm just making this up), and he told me that right up there with all the other unstoppable so-unbelievably-massive-you-don't-think-it's-possible changes sweeping the world is how China's gender imbalance will soon make young Chinese women among the world's rarest commodities. Yes, all hundreds of millions of young Chinese women will be relatively scarce.

[Today I read about quality on top of the quantity effect. To be clear, this is a parody of Amy Chua - so this part in brackets at least is in jest).]

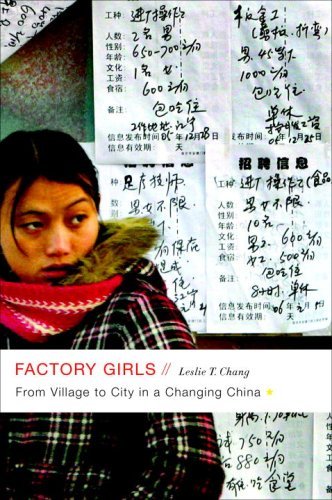

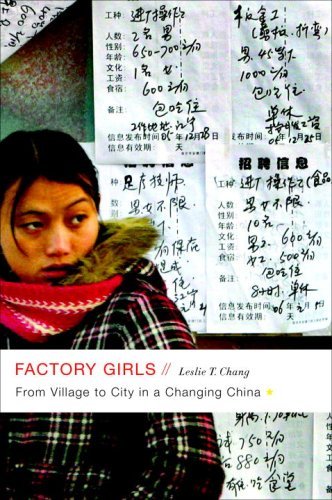

Hand in hand with this increase in the market's shadow price - economic power - will be a steep escalation in the real power of women, both personal and political. This is not to deny the harrowing experiences documented in Leslie Chang's Factory Girls but there is, at the same time, no question that there has been a dramatic upgrading of the position of women throughout Asian society, and therefore of women worldwide.

No legislation was involved. No protest movement occupied a city square. All this occurred simply through the power of economic growth, the balance between demand and supply, and the force of market equilibration. If you don't yet see this, just come take a look at the confidence, poise, and ambition of the tens of thousands of young Mainland Chinese women studying in secondary schools, junior colleges, and universities in Singapore, elsewhere in Southeast Asia, or in the West. Come take a look at LSE, for that matter.

Perhaps once again China's headlong rush for economic growth and the staggering power of markets adjusting to demand and supply in the hundreds of millions will quietly, brilliantly do what the rest of the world has found so difficult. China lifted over 600 million people out of extreme poverty over the last quarter of a century, when no one else was looking - and therefore when no one was giving China foreign aid or telling it how to run its schools.

This time, for elevating yet another disadvantaged community will China, once again, quietly using just growth and markets achieve more than all other efforts micro-managing around the edges of global poverty?

PS Many readers, of course, quickly link in their mind this gender imbalance to the many horrific tales one hears emerging from China's one-child policy. If 119 boys are born for every 100 girls - as usually reported for China - then that works out to 840 girls to 1000 boys. Given China's population of 1.3 billion, this means 24 million Chinese men of marrying age without spouses by 2020.

It is instructive if grim to note this gender bias is seen as well in the very differently-governed India where the 0-6 age group now has 914 girls to 1000 boys (down from 927/1000 in 2001), confirming how the country has become "a terrifyingly hostile place to be conceived or born a girl", pointed out to me by Vinayak @kayaniv.

Wednesday, April 20, 2011

Not what is good for the West but for the world

That's what I should have written up front in The Shifting Global Balance of Power.

Friday, July 30, 2010

The global economy's shifting centre of gravity

Friday, July 17, 2009

Time to save the world economy through the sheer weight of numbers

Will China save the world?

No one can yet be sure how these latest developments will play out. Of course, upon hearing good news of this kind, nay-sayers are quick to relate how a more pessimistic picture is indicated by other numbers. [Power consumption is usually a good fallback for this - although it's not clear to me which fully fleshed-out economic theory says why that is so.]

Or some say that the good news is likely just unsustainable short-term hot money channeling into propping up only temporarily asset markets and bank lending. [Come to think of it, except for long-term trend growth, doesn't every kind of aggregate demand expansion simply prop up asset markets in the short run? And isn't increasing bank lending exactly what we're trying to do elsewhere in the world? Unsuccessfully at that? At the end of it all, any action that releases 4 trillion units of anything - such as that China has undertaken with its fiscal expansion - has got to have some slippage.]

Finally, there's that portmanteau standby: "I just don't trust these numbers," instantly killing all intellectual debate. That one never grows old.

Perhaps the ambiguity in the current numbers is genuine. So look elsewhere: a historical perspective might be useful.

The 1997 Asian Currency Crisis was, up through 2008, perhaps yet the most wrenching financial and economic crisis in East and Southeast (ESE) Asia. In its concentrated impact on the region, 1997 might well have been just as severe as 2008/2009 for ESE Asia. From June 1997 to mid-January 1998 exchange rates against the US dollar of the currencies of Indonesia, South Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand fell by over 50%; that of Singapore, 20%. In Japan and in every single one of these economies, GDP growth turned negative in 1998, with the combined fall in these economies' 1998 GDP amounting to 2.4% of GDP in ESE Asia the preceding year. Millions of people lost their jobs.

So, if you had been following developments in fast-growing ESE Asia up through before 1997, were then shocked by 1997's sweep through the region, what should you have expected for how wrenching these losses were and how much they perturbed that region's growth path? Here's a graph of the fitted trend line through 1996 of GDP in ESE Asia (excluding Japan), then projected forwards and compared to reality post-1997:

The striking feature in this chart is how little a change in the growth path resulted from what at that time was viewed to be a dramatic downturn. Sure, the accumulated GDP under-performance from 1997 to 2006 was 5.1%. But the same calculation for the world economy overall was 11%, more than double that for ESE Asia, although the world's pre-1996 growth rate was only 3.7% a year in contrast with ESE Asia's 7.6%. Even before the 2008 global financial crisis, the world overall had slowed in comparison to the 4 decades before 1997. But ESE Asia, the centre of that period's financial crisis, emerged far better than one might have expected then.

The striking feature in this chart is how little a change in the growth path resulted from what at that time was viewed to be a dramatic downturn. Sure, the accumulated GDP under-performance from 1997 to 2006 was 5.1%. But the same calculation for the world economy overall was 11%, more than double that for ESE Asia, although the world's pre-1996 growth rate was only 3.7% a year in contrast with ESE Asia's 7.6%. Even before the 2008 global financial crisis, the world overall had slowed in comparison to the 4 decades before 1997. But ESE Asia, the centre of that period's financial crisis, emerged far better than one might have expected then.Or did it? If we exclude not just Japan but also China from ESE Asia, the graph that emerges is quite striking and a little scary:

the accumulated under-performance is then 21%! Through sheer size and economic performance, the significance of China should have been observable even from outer space. This importance of China in aggregate economic performance mirrors its single-handed reduction of the world's poverty over the last three decades (that I've blogged on previously).

the accumulated under-performance is then 21%! Through sheer size and economic performance, the significance of China should have been observable even from outer space. This importance of China in aggregate economic performance mirrors its single-handed reduction of the world's poverty over the last three decades (that I've blogged on previously).To emphasize further this historical point, recall that prior to 2008 the last two times the US economy went into recession was 1991 and 2001: in 1991 US GDP fell $13.7 bn. In 2001 US GDP grew US$74.1 bn. By contrast, ESE Asia generally and China in particular continued to grow throughout. Taking absolute values, and comparing these changes with those elsewhere gives this table:

All data here are in constant 2005 US dollars, evaluated at market exchange rates, not purchasing power parity - so the denomination in this comparison is what the whole world would use to buy wide-body Boeing jets, Nokia cellphones, and Italian fashion design.

All data here are in constant 2005 US dollars, evaluated at market exchange rates, not purchasing power parity - so the denomination in this comparison is what the whole world would use to buy wide-body Boeing jets, Nokia cellphones, and Italian fashion design.True, in this comparison, China's per capita income now stands at only 1/14th that of the US; in aggregate, the US economy is still one quarter that of the entire world. But even so and even over relatively long stretches of time (2002-2006) China was already contributing more than half of the growth to the world economy that the US was doing. In times of US and world downturns, however, that ratio rises dramatically: China contributed 3 times what the US failed to do in 1991 (again, using the absolute value of the US change in income), nearly one and a half times the US's contribution in 2001.

Indeed, the rise of China [and to a smaller extent India] since the early 1980s has shifted the world's economic center of gravity 1800 km - 1/3 of the planet's radius - deeper into the Earth's crust, away from the US, and towards the East (previously blogged). This transition accelerated in 1991 and 2001, each time the US was in recession.

So, perhaps this time, it won't surprise that China leads the world economy out of recession. After all, it's already done so before, quietly.

Notes: I met John Ross recently, when he and I spoke on a panel on London and the global economic crisis, but hadn't seen his recent post on China's dramatically shrinking trade surplus, making a similar and more current point than my own post here. I highly recommend his posting.

All data are from the World Bank's World Development Indicators 2008. I provide more details on the numbers I've described above in my paper, "Post 1990s East Asian economic growth" (October 2008; also Spanish translation in pp. 40-52, Claves de la Economia Mundial 2009, Instituto Espanol de Comercio Exterior, Secretaria de Estado de Comercio, Ministerio de Industria, Espana www.icex.es).

Thursday, May 28, 2009

One quick look at the world's shifting economic centre of gravity

At Hay Festival last weekend I appeared together with Howard Davies on a panel discussing the global economic crisis. For that and for some work (teaching, writing) that I'm doing on the global economy, I prepared this animation:

(A somewhat fuller-sized animation appears on my econ.lse site... but then we are talking about the world, so, despite the best efforts of Google Earth, anything on a computer screen will always be a little too small and representational.)

Obviously, a few more things need still to be thought through on this but for now the flat-world map animates the shift in the world's economic centre of gravity (building on calculations by Jean-Marie Grether and Nicole Mathys). The rise of China and India since the early 1980s has shifted the world's economic center of gravity 1800 km - 1/3 of the planet's radius - deeper into the Earth's crust, away from the US, and towards the East. The transition accelerated in 1991 and 2001, each time the US was in recession.

It might seem peculiar that the world's economic centre of gravity is so far north - is there some massive production going on near the North Pole that the world's military haven't told us about? No, that feature comes instead from how the 2-dimensional flat map has to represent something going on in a 3-dimensional spherical Earth. Suppose, for illustration, that Earth has two roughly equal centres of production at the same latitude just north of the equator but on the same great circle. Their centre of gravity is at that same latitude but deep within the Earth. Then, when you project a straight line from the Earth's centre to that centre of gravity and keep going until you burst out of Earth's surface, you come out quite far north - certainly further north than those two production centres were to begin. So, as long as most of Earth's production occurs in the Northern Hemisphere and aren't all closely located to each other so that only one side dominates, projection onto a 2-dimensional flatmap always shows the centre of gravity on the Earth's surface appearing quite far north.

Although it's not, strictly speaking, an error, I do think some re-definition of concepts would be useful. That's something I'm trying to fix now.

PS I've already referred to my paper on post-1990s East Asian economic growth elsewhere on this blog but, yes, that article contains more detail on the effects described in the animation.

Sunday, November 16, 2008

Where in the world is Asian Thrift and the Global Savings Glut?

Sometime in the early 1990s the US began to move its international trade account from approximate balance into burgeoning deficit. From then on the US trade deficit grew year on year so that by 2006 the US consumed nearly US$900 billion more than it produced.

Such excess amounted to 7% of US GDP—up from an average of 2% over 1990–1994. For perspective, the US trade deficit in 2006 was nearly as much as the entire annual production of goods and services in the 1.1 billion-peopled economy of India (this was an improvement, though: in 2005, the US deficit was strictly greater than India’s GDP). And a 7% ratio is the same as that Thailand had in June 1997 on the eve of the run on the Thai baht precipitating the Asian currency crisis.

Except for the possibility of trade with outer space, the US deficit has to be matched dollar-for-dollar by trade surpluses in the rest of the world. Correspondingly, therefore, the rest of the world has been saving—consuming less than it has been producing—and accumulating dollar claims against the US as a result.

In this description, however large the global imbalance, a savings glut—wherever or however it might arise on Earth—has no independent existence. It makes as much sense to say the world’s excess savings caused enthusiastic US consumers to flood into Walmart to buy $12 DVD players, as to say US consumer profligacy made hungry Chinese peasants abstain even more and instead plow their incomes into holdings of US Treasury bills.

When two variables have always-identical magnitudes, obviously neither can usefully be said to cause the other. With global savings and consumption, however, looking at a third indicator, namely world interest rates, is suggestive. The Figure shows world money market interest rates falling sharply through the 1990s, as would be suggested by a global savings glut driving the large global imbalance.

(The Figure is for short-term nominal interest rates. Charting this for real long-term rates accentuates the fall. Subtracting actual inflation to construct real short rates makes the decline less obvious although not vanish. But I’m going to dispute this reasoning next anyway, so let’s keep the Figure.)

Many other factors could, of course, have driven down short rates: US monetary policy responded to national economic downturns in 1991 and 2001. Through the 1990s inflation rates worldwide converged and fell, together with short-term interest rates set by central banks everywhere. The burst of the dot-com bubble in March 2000 saw the NASDAQ index decline 77% in the following 18 months, prompting action by the US Federal Reserve. Japan’s monetary policy during its decade-long recession drove nominal interest rates there to zero.

It seems useful to obtain additional evidence on whether the global imbalance was indeed driven by a global savings glut or, in some interpretations, Asian thrift.

The Figure shows that, indeed, Developing Asia in general and China in particular, were running large and growing bilateral trade surpluses against the US.

The next Figure, however, shows that running trade surpluses against the US was pretty much the pattern nearly everywhere in the rest of the world. Both the EU and the bloc of oil-exporting countries, had rising bilateral trade surpluses against the US too, although of course the notion of “EU Thrift” has hardly ever been bandied about in international relations. Summed, the EU and oil-exporters trade surplus against the US moved almost exactly in step with that of China’s.

Dwindling investment opportunities and an aging population in Europe might, indeed, over the longer run, smoothly and gently, end up pushing greater savings in the direction of the US. But why would those same persistent movements cause higher-frequency gyrations in the EU’s trade surplus against the US that match almost exactly that of China’s in particular and Asia’s more generally? It seems to me the most direct and straightforward explanation is that the causal impulse to these trade surplus dynamics is instead the US economy, and everyone else is simply passively responding.

Indeed the ratios to the overall US trade deficit of individual country bilateral trade surpluses—run by each of China, Developing Asia, the EU, and the oil exporters—have time-series profiles that, after the mid-1990s, were essentially flat. Sure, China's and Asia's trade surpluses against the US were large and growing. But they were growing only because they remained roughly constant in proportion to bilateral trade surpluses elsewhere and, more to the point, to the US overall trade deficit.

So, yes, of course, there was a global savings glut. It necessarily mirrored exactly US profligacy, both private and public. Looking at these last few Figures, however, one might be tempted to think that excesses in the US economy drove trade surpluses everywhere else in the world, rather than that causality ran from Asian thrift to US trade deficit.

The reality, however, is almost surely that some combination of factors—central bank policy, Asian thrift, US consumer profligacy, US government actions, cheap East Asian goods resulting from a low-wage yet productive workforce (which must be a good thing surely)—was responsible for the large global imbalance of the early 2000s. To put the blame monocausally on Asian Thrift seems both irresponsible and inconsistent with the facts. And it is important to get to the root of this: the resulting global imbalance and its associated massive flows of financial assets likely led to the extreme financial engineering that now everyone claims no one responsible ever really understood in the first place.

In producing the Figures above I found useful the data and discussions in Ben Bernanke (2007) “Global Imbalances: Recent Developments and Prospects”; Thierry Bracke and Michael Fidora (2008) “Global liquidity glut or global savings glut”; Menzie Chinn and Jeffrey Frankel (2003) “The Euro Area and World Interest Rates”; Niall Ferguson (2008) “Wall Street Lays Another Egg”; Paul Krugman (2005) “The Chinese Connection”; Kenneth Rogoff (2003) “Globalization and Global Disinflation”; and Brad Setser (2005) “Bernanke's global savings glut”.

Daniel Gross (2005) “Savings Glut” traces the history of the idea that a global savings glut is to blame for many current US economic ills. The subtitle (The self-serving explanation for America's bad habits) reveals the conclusion that Gross reaches. Fareed Zakaria (2008) “There is a silver lining” describes the profligacy of the US consumer and government since the 1980s, and how the current global economic crisis might turn that around. He remarks that the US “cannot noisily denounce Chinese and Arab foreign investments in America one day and then hope that they will keep buying $4 billion worth of T-bills another day.”

The data I used are from the World Bank's World Development Indicators (WDI) Online, April 2008; and International Monetary Fund (IMF), Direction of Trade Statistics (DOTS) and International Financial Statistics (IFS), November 2008, ESDS International, (MIMAS) University of Manchester.

(This post also appears 21 November 2008 on RGE's EconoMonitor on Global Macro and Asia. See also December 2008 discussion on the FT Economists' Forum on global imbalances.)

Sunday, April 06, 2008

Who moved my BlackBerry... and those hundreds of millions of people?

A related not uncommon view further has it that India codes workman-like software, designs lower-end pharmaceuticals, answers queries about insurance claims over the telephone, and scans X-rays that Western doctors are too busy to do. These jobs might pay far less than done in the West but, in their part of the global marketplace, they almost surely pay better than stitching together textiles in Shanghai (上海) or assembling refrigerators in Shandong Peninsula (山东半岛).

So, which economy has had its growth driven more by changes in labour input? Where have more people moved out of poverty?

The Figures (using data kindly provided me by Dale Jorgensen and Khuong-minh Vu that they had used in their paper "Information Technology and the World Economy", 2006) show decompositions of Chinese and Indian growth into contributions due to physical capital, labour, and productivity (TFP). Earlier on, between 1989 and 1995, China certainly drew more on labour than did India to power economic growth and, true to stereotype, drew more on labour hours ("mere sweat and effort") than on labour quality, i.e., on skills and human capital. But even then the difference was small.

The Figures (using data kindly provided me by Dale Jorgensen and Khuong-minh Vu that they had used in their paper "Information Technology and the World Economy", 2006) show decompositions of Chinese and Indian growth into contributions due to physical capital, labour, and productivity (TFP). Earlier on, between 1989 and 1995, China certainly drew more on labour than did India to power economic growth and, true to stereotype, drew more on labour hours ("mere sweat and effort") than on labour quality, i.e., on skills and human capital. But even then the difference was small.

By 2000-2005 the most recent period for which we have data, China had come to rely more on physical capital, i.e., on machines. Its reliance on labour had fallen to 13%, almost exactly half that of India's. That shift occurred, moreover, with little loss in productivity's contribution. Through both periods and in both countries, productivity never contributed less than 40% of growth overall.

By 2000-2005, in fact, China's profile of growth contribution from capital, labour, and productivity almost exactly matched that of the US. The difference, of course, is that China has been growing at 3 times the rate of the US.

By 2000-2005, in fact, China's profile of growth contribution from capital, labour, and productivity almost exactly matched that of the US. The difference, of course, is that China has been growing at 3 times the rate of the US.The next Figure (per capita income on the horizontal axis; hundreds of millions in $1/day-poverty) shows

how China's much, much more impressive aggregate growth has lifted half a billion people out of extreme poverty in the last quarter-century; India, on the other hand, has only recently and, by comparison, imperceptibly started along the same path. But with a long way to go still. The data are for 1984-2004; I had used them in a previous blog posting.

how China's much, much more impressive aggregate growth has lifted half a billion people out of extreme poverty in the last quarter-century; India, on the other hand, has only recently and, by comparison, imperceptibly started along the same path. But with a long way to go still. The data are for 1984-2004; I had used them in a previous blog posting.My own small contribution on global inequality the last couple months was extremely practical. I did what I could in charitable fundraising. The video shows my friend Maria Gratsova holding the board for an airbreak. I performed a jump spinning hook kick. This particular event was the LSE Development Society auction on 05 February 2008, and I was up on the auction block. Fortunately, someone did buy me - for much more than I'm worth. But the money went to a good cause and the deal was that we had a paid-for dinner together afterwards.

(Yes, yes, I know, boards don't hit back but an airbreak means the board swings loose, and so is harder to break. And of course that they don't hit back doesn't mean they break everytime. In this next video [from September 2007] I attempted two boards on one jump and only broke one.)

Thanks to the kindness of friends, Maria and I held a repeat performance at LSE's Malaysia-Singapore Students Night, 23

February 2008, in the Old Theatre. Money changed hands there too, and for just as worthy a cause. (This still is from LiEe Ng's camera; thanks LiEe!)

February 2008, in the Old Theatre. Money changed hands there too, and for just as worthy a cause. (This still is from LiEe Ng's camera; thanks LiEe!)

Saturday, September 01, 2007

Global balance and equality

I wanted to show the large forces that drive global inequality and poverty, those changes that affect, in one fell swoop, the quality of life for many of the 6.3 billion people on earth.

I have two candidates for massive worldwide change: First, economic growth; second, China. The graphic illustrates both.

(a larger dynamic animation can be invoked if the inline version above isn't clear enough in your browser; or just click anywhere in the figure).

The vertical axis measures millions of people living on less than 1 US dollar a day (actually, the threshold is 1 International Dollar a day, but close enough). The horizontal axis is per capita income in the country or bloc of countries: Economic growth means movement rightwards horizontally. The size of a bubble measures the total population. EAP indicates East Asia and the Pacific Region; LAC, Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA, Middle East and North Africa; SAS, South Asia; and SSA, Sub-Saharan Africa. Additionally, China and India are given separately in the graphic.

The animation follows these continental groupings over time, from 1990 through 2004, and shows how as growth occurs, poverty falls.

In principle, if inequality within a continent or within China or India increased sufficiently with economic growth, then the corresponding bubble in the picture might well rise vertically. All that means then is that, in that case, even though average income increases with growth, inequality increases so overwhelmingly that the joint growth-inequality process grinds ever more people into ever greater bone-crunching poverty.

(To be clear, inequality does not have to increase with economic growth. But many people and quite a few economists think it might---hence the so-called tradeoff between equality and efficiency. The data do not speak very strongly on this, in either direction. But I think such a putative regularity is of little consequence for the point here.)

Almost uniformly, the graphic shows inequality is unable to rise enough to overcome the benefits of economic growth. As a matter of logic alone, of course, it might: an actual, large instance in the animation is China between 1996 and 1999: In that 3-year period the China bubble moved rightwards and upwards. So there's nothing in the arithmetic that rules out the possibility. But it is unusual. As time proceeds, almost uniformly, the bubbles move southeasterly, shifting rightwards and dropping towards the floor. This is a very good thing. Economic growth reduces poverty.

In the animation, right at the start of the sample Eastern Europe and Central Asia (ECA) implodes leftwards, just as post-Communist transition began. But then after that pretty much only the rightwards movement is visible. Compared to China, that other 1-billion people economy India, up through 2004, still hadn't done very much. Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) all this time basically did nothing but percolate upwards: It didn't grow and it saw vast numbers of its people fall ever further into grinding poverty.

In 1981 1.47 billion people on earth lived on less than 1 dollar a day. By 2004 that number had fallen to 0.97 billion, a reduction of half a billion. (If you don't like these numbers, you come up with better ones. In economic research it takes a model to beat a model, so simply complaining that a model isn't a good model or is unrealistic doesn't get you very far. So too whining that an estimate isn't a good estimate.) The animation shows that pretty much all of that worldwide poverty reduction is due to just ... China.

Since this animation, like all digital goods, is infinitely expansible, I also presented it at a British-Malaysia Chamber of Commerce lunch and as part of a lecture at the British Council in Malaysia, both also in August, as part of Malaysia's 50th anniversary celebration of its independence from Britain. (The animation is also on youtube and you can put a version on your cellphone if you like.)

The underlying data are from Chen and Ravallion (2007) "Absolute Poverty Measures for the Developing World" and from World Development Indicators (2006) online. Further analysis is in Quah (2007) "Life in Unequal Growing Economies". Related discussion appears in Quah (2003) "One Third of the World's Growth and Inequality".

I generated the animation by

latex 2007.08-SERC-lug-dq.tex

dvips -pp 5-10 -o - 2007.08-SERC-lug-dq.dvi | ps2pdf - - | convert -delay 80 - 1-2007.08-SERC-lug-dq.gif

i.e., using standard tools

latex, dvips, ps2pdf, and convert.